Daniel Sponheimer, Catella Investment Management

The new version of the European Building Directive (EPBD) brings about a fundamental change in the way energy performance certificates are handled. With the amendment adopted in the spring, the EU is pursuing the goal of making the energy consumption of buildings more comparable across all member states. A central role is played by the recalibration of the so-called Energy Performance Certificates, or EPCs for short, which are to be issued uniformly from class A to G in the future.

While it was previously up to each member state how the energy classes were determined, the new regulation provides for a mandatory reference. In the future, class G will basically represent the 15 percent of buildings with the worst energy balance within a country. Class A is reserved for so-called zero-emission buildings, which will become mandatory for new buildings. In between, new Europe-wide harmonized classes are being created, which are not only more comparable, but also bring with them digital availability, standardized color scales and uniform data bases.

This new logic will have noticeable consequences for real estate investors. Buildings that are still considered to be energy-average today can fall into lower classes with the rescaling. This will be particularly problematic for assets that will be classified in class F or G in the future. They will then be subject to the so-called minimum energy performance requirements, as regulated in Article nine of the new EPBD. These requirements apply in particular to new rentals or sales and, in practice, lead to technical retrofitting becoming mandatory. The energy performance certificates are thus no longer only understood as an information instrument, but as a concrete steering element of European climate policy.

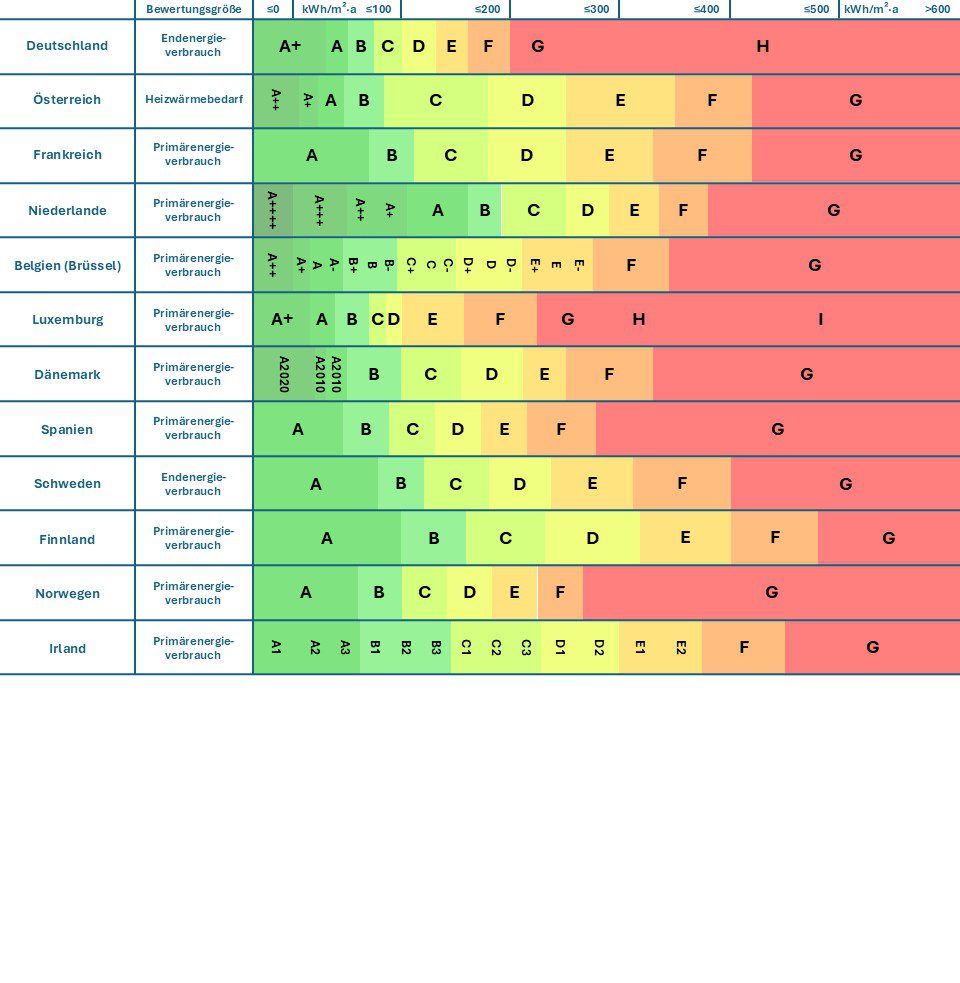

Especially for funds with pan-European real estate portfolios, the changeover brings new uncertainties. Although uniform classes are planned throughout Europe in the future, today’s starting points are extremely different. In Germany, the scale currently ranges from A+ to H, based on total energy consumption in kilowatt hours per square metre per year. France, on the other hand, has so far only used A to G, but is based on primary energy demand. In Belgium – at least in the Brussels capital region – there are more than 15 subclasses in use, from A++ to G, including intermediate levels such as B– or E+. The Netherlands is the only country to have even introduced class A++++ in order to be able to map emission-free buildings in a more differentiated way.

In Denmark, buildings are currently classified according to a year system. There are categories such as A2020, A2015 and A2010, each of which has different consumption limits, which are also linked to the size of the building. Ireland distinguishes between A1 and A3 and classifies buildings in finely structured energy bands up to G. In Sweden, on the other hand, the classification has so far been based on relative comparative values to the national reference standard. Here, the EPC classes correspond to a percentage of the maximum permissible consumption, which makes direct cross-border comparisons difficult. Norway and the United Kingdom, on the other hand, use CO₂-based indices, with consumption data often shown additionally.

This fragmentation means that the same energy class can reflect very different real consumption values in different countries. A building with class A in France can be much more economical than a property with class A in Germany or Spain. This is exactly where the planned harmonization of EPCs should start. In the future, uniform scales and thresholds are not only intended to create more transparency, but also a common regulatory framework of reference that is reliable for investors and asset managers across national borders.

The digital structure of the new EPCs plays a central role in this. In the future, energy performance certificates are to be recorded in electronic registers, made available nationally and linked to each other in the long term. It is therefore becoming more important for investment management companies to set up reliable data systems and interfaces that can process this information automatically. After all, in an environment in which sustainability and energy efficiency are increasingly closely linked under regulatory law, the availability, quality and comparability of this data is crucial – not least for the implementation of the taxonomy, for ESG disclosure under SFDR or for strategic restructuring management.

The harmonisation of energy performance certificates is a logical step on the way to greater transparency and controllability in the building sector. At the same time, the demands on owners, asset managers and investors are increasing. If you want to keep your portfolio strategically fit for the future, you need to understand early on what the new classification means in concrete terms. After all, in a system that automatically sanctions the buildings with the worst energy efficiency, it is not only the technology that is decisive, but also the ability to interpret regulatory signals correctly – and to derive the right measures from them.

🛈 Note on comparability:

All energy classes shown are based on the annual primary energy consumption in kWh/m² and refer to multi-storey residential buildings. In countries whose energy performance certificates originally use a different valuation parameter , the values have been converted in a standardised manner for better comparability:

- Austria: The heating demand (HWB) was converted into primary energy consumption with a conversion factor of 1.8 .

- Sweden: Final energy consumption has also been approximated by a factor of 1.8 to primary energy consumption.

The conversion is based on common energy assumptions for residential buildings and enables a uniform representation within the framework of a Europe-wide scale.