Space requirements for defense

There is movement in the market again. Special real estate funds are being opportunistically examined, and initial allocations are being discussed. Between logistics, industrial light and infrastructure, a topic that has long been avoided is resurfacing: defense.

What is currently being sighted is not weapons production. It is mainly about defensive real estate: logistics, storage and maintenance space, often in project companies, often with long-term leases – in some cases with state users. This can sound interesting: stable cash flow, long term, supposedly high predictability.

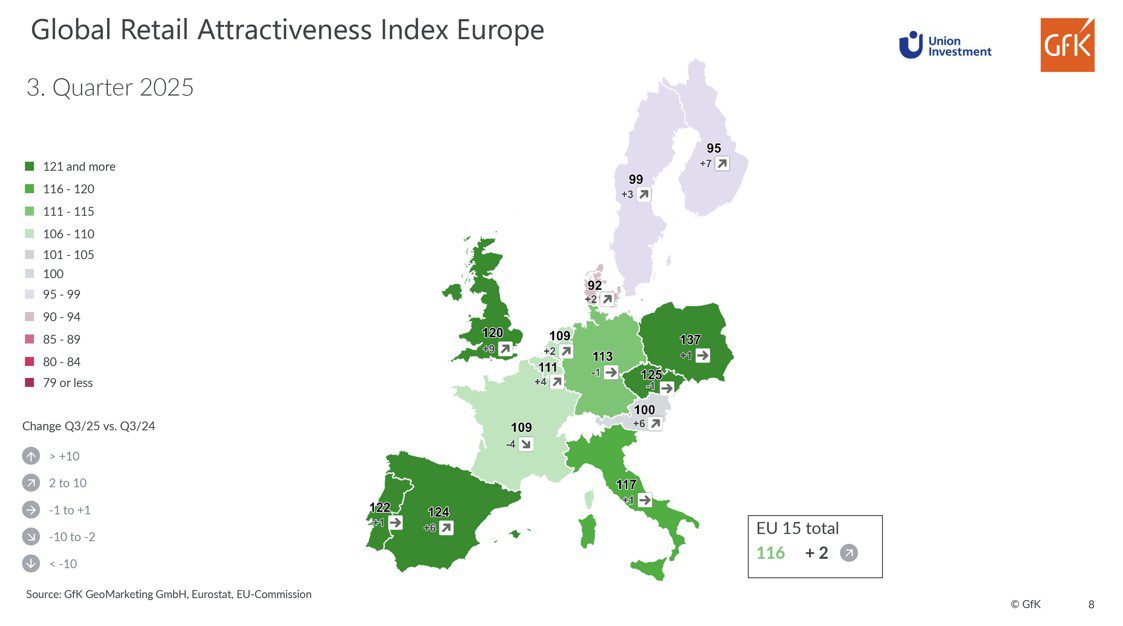

The macro tailwind is also real. According to an analysis published by Savills in 2025 , rising defence spending and new NATO commitments could trigger an additional demand of up to 37 million m² of industrial and logistics space in Europe and the UK by 2033 – of which around 6 million m² is in Germany. It is based on NATO’s new target of allocating 3.5% of GDP to core military competencies, which would correspond to an increase in demand of around 17% compared to 2024.

Space requirements alone are not a fund product

This assessment coincides with the view of several market observers and analysts. Defence is increasingly being classified as a structural demand driver for industrial and logistics space – but not so much through classic final production (i.e. weapons production), but above all through equipment procurement, upstream value creation stages and security-relevant logistics. At the same time, it is pointed out that the requirements for locations and buildings are highly specialized: security, authorization, spatial separation and sometimes remote locations often take precedence over classic logistics parameters such as third-party usability or connectivity. Accordingly, a large part of the resulting demand for space is accounted for by owner-occupiers, while the proportion that can be invested institutionally remains limited.

Defense real estate is therefore not standard logistics. They are highly specialized, security-relevant and often location-bound. Especially where, for example, state users such as the Bundeswehr appear, the logic of connection and third-party exploitation remains a relevant topic – especially in rural regions whose choice of location was primarily based on military and not market economy criteria.

It is true that such leases often reach terms of 20 years and thus sometimes give the fund profile characteristics of social infrastructure, especially for state users. But even long terms are no substitute for sustainable location and exit logic: What appears stable during use can quickly become a valuation and liquidity problem after the end of the contract.

Even in the case of newly built build-to-suit properties, the CAPEX issue is not eliminated, but is brought forward in the purchase price. In the case of very long leases, the risk shifts from the construction phase to the lifecycle – and thus from the question of the initial equipment to the question of who pays for adjustments and technological renewal over the term.

Cautious inclusion of Defense in existing fund products

The market is acting accordingly cautiously. Defense now appears in individual industrial strategies and occasionally also in club deals. However, large, established funds usually clearly limit such exposures – often to a smaller addition to the portfolio. This is not so much an expression of a lack of opportunism as the result of clear consideration for existing investor structures. Because even if Defense has become more socially acceptable, it remains problematic for some investors from an attitude perspective.

A look at the EU regulatory landscape sharpens the classification. The EU-Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) does not prohibit investments in the defence sector across the board. The European Commission has clarified in an official Commission Notice that the EU Sustainable Development Framework is in principle compatible with investments in defence activities and does not provide for a sectoral exclusion logic; rather, each investment must be examined on a case-by-case basis.

This is precisely where the crucial point lies: While the regulatory framework does not draw a general red line, some investors are still indifferent with their own assessment. In particular, church and value-based investors categorically rule out leasing to arms or defense companies – regardless of term, creditworthiness or expected return. ESG is less a regulatory matter than an attitude here – and can therefore be a real show-stopper for specific investors.

📌 Conclusion

👉 Defense is not yet an independent real estate label.

👉 So far, it has worked more as a dosed admixture within broad industrial or infrastructure strategies

👉 . Due to the specifics of Defense, clear exit logic, transparent communication and more resilient asset management expertise are crucial in investor screening.