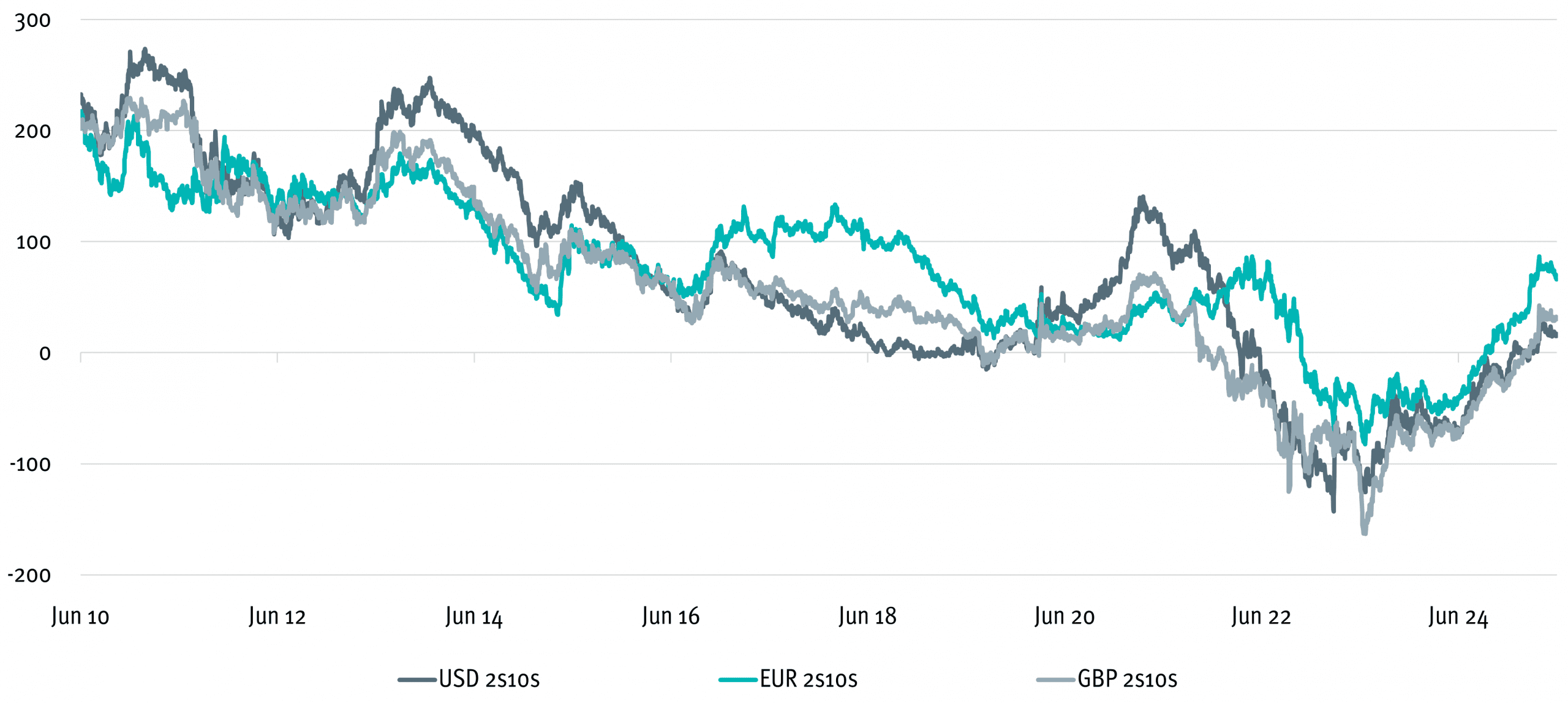

Since mid-2024, we have seen a steady and rapid rise in yield curves in the US, UK and Europe. As an example, the chart shows the yield curve between two- and ten-year swaps. Of course, this is because we are in a rate cut cycle. After the rapid rise in key interest rates in response to global inflation, the curves also started from strongly inverted levels. So a certain normalization was definitely necessary.

For some months now, however, the focus has increasingly shifted back to fiscal policy and swelling deficits. The USA will continue to report an annual deficit of more than 6 percent in the coming years, while in Great Britain the budget will become tighter and tighter with every rise in interest rates, although investments are already calculated out of the deficit limit. France’s situation was already covered in the last issue of our newsletter, and even Germany is suspending its debt brake.

At a time when interest rates are close to 0 percent and inflation is too low, most governments have become accustomed to not having to fear consequences for additional debt. Stimulus in times of crises such as Covid also makes perfect sense, only times have changed. In many countries, annual spending on interest is now higher than the budget for defense or education. The refinancing costs of the high debt legacy continue to drive up the deficits and there is a risk of a “doom loop”. The increased supply of government bonds is offset by falling demand from pension funds and insurance companies, especially at the long end.

Swelling deficits and political uncertainty are steeping the curve.

A consolidation of public finances does not seem politically possible, so the market must find a “clearing level” for the increased financing needs. Warnings about the so-called “bond vigilantes” – international investors who sell government bonds and thus restore fiscal discipline – are getting louder. What this looks like could be observed in the UK in 2022. After PM Truss’s now famous “mini-budget”, interest rates on 30-year gilts shot up by almost 1.5 percent before the BoE had to intervene with bond purchases. The eurozone crisis in 2010/11 can be cited as another example, and even President Trump only cut his tariffs when the bond market began to wobble.

However, the examples just mentioned also show that states are not defenceless against the “bond vigilantes”. They certainly have ways and means to at least cushion the rise in interest rates at the long end. First, national financial agencies can issue less long-dated bonds and thus address the aforementioned supply-demand imbalance. This is the path taken by Great Britain, for example, where the average maturity of new government bonds has fallen dramatically, from 20 years in 2018 to just 9 years. Japan recently announced the same path when 30-year government bonds rose to over 3 percent. And US Treasury Secretary Bessent’s criticism of his predecessor Janet Yellen for issuing too many bills and too few bonds has also been heard since he took office.

In the USA in particular, regulatory requirements are also being put to the test, with the aim of creating more capacity for banks to buy government bonds (keyword SLR reform). The last option is direct purchases by central banks (QE), as in the UK in 2022 or Draghi’s courageous intervention in the eurozone crisis.

The attentive reader will have noticed that these approaches alone do not solve the basic problem, but at best postpone the appropriate market reaction and at worst drive up inflation, which in turn would further reduce demand for long bonds.

Global yield curves – normalization or new trend?

The concept of “term premium” illustrates this component. It is defined as the extra interest rate that investors charge to buy a long bond instead of (re)investing in a series of short-term bonds. As such, it is driven by uncertainty about future central bank policy and inflation. At the same time as the curves have risen, the term premium has also risen significantly, but historically it is still below average, especially compared to the period before the financial crisis.

This situation is leading to the current power struggle between market participants, who demand more compensation for their risk, and governments, which have to finance their swelling deficits. In the long term, the mountains of debt can only be reduced through increased growth and higher inflation, which becomes a dilemma for central banks and should contribute to the further steepening of the curves.